October 2, 2013

This Alkaline African Lake Turns Animals into Stones

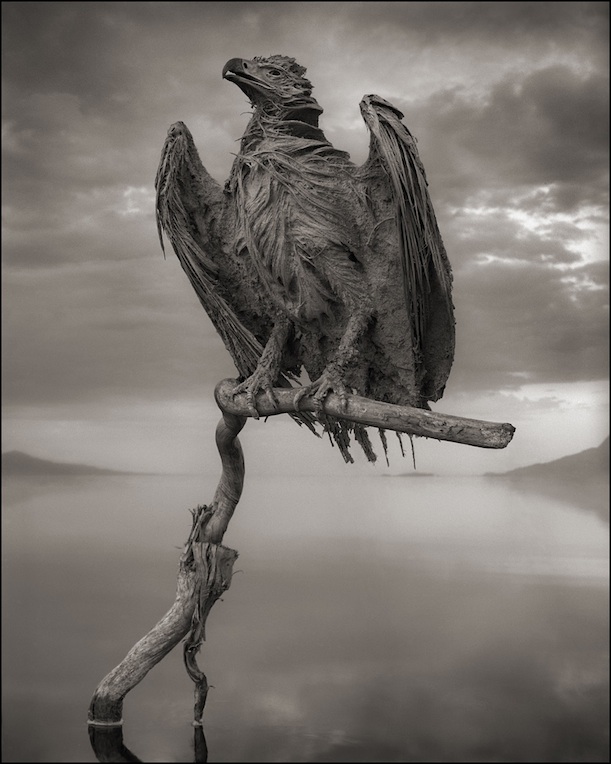

A calcified flamingo, preserved by the highly basic waters of Tanzania’s Lake Natron and photographed by Nick Brandt. © Nick Brandt 2013, Courtesy of Hasted Kraeutler Gallery, NY

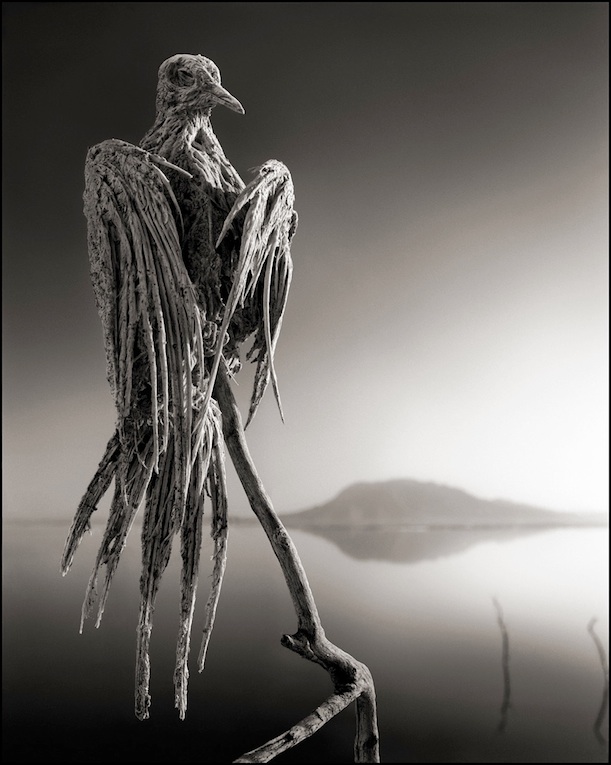

“When I saw those creatures for the first time alongside the lake, I was completely blown away,” says Brandt. “The idea for me, instantly, was to take portraits of them as if they were alive.”

A bat © Nick Brandt 2013, Courtesy of Hasted Kraeutler Gallery, NY

Unlike those other lakes, though, Lake Natron is extremely alkaline, due to high amounts of the chemical natron (a mix of sodium carbonate and baking soda) in the water. The water’s pH has been measured as high as 10.5—nearly as high as ammonia. “It’s so high that it would strip the ink off my Kodak film boxes within a few seconds,” Brandt says.

A swallow © Nick Brandt 2013, Courtesy of Hasted Kraeutler Gallery, NY

Frequently, though, migrating birds crash into the lake’s surface. Brandt theorizes that the highly-reflective, chemical dense waters act like a glass door, fooling birds into thinking they’re flying through empty space (not long ago, a helicopter pilot tragically fell victim to the same illusion, and his crashed aircraft was rapidly corroded by the lake’s waters). During dry season, Brandt discovered, when the water recedes, the birds’ desiccated, chemically-preserved carcasses wash up along the coastline.

“It was amazing. I saw entire flocks of dead birds all washed ashore together, lemming-like,” he says. “You’d literally get, say, a hundred finches washed ashore in a 50-yard stretch.”

A songbird © Nick Brandt 2013, Courtesy of Hasted Kraeutler Gallery, NY

Just coming into contact with the water was dangerous. “It’s so caustic, that even if you’ve got the tiniest cut, it’s very painful,” he says. “Nobody would ever swim in this—it’d be complete madness.”

A fish eagle © Nick Brandt 2013, Courtesy of Hasted Kraeutler Gallery, NY

A dove © Nick Brandt 2013, Courtesy of Hasted Kraeutler Gallery, NY

***

No comments:

Post a Comment