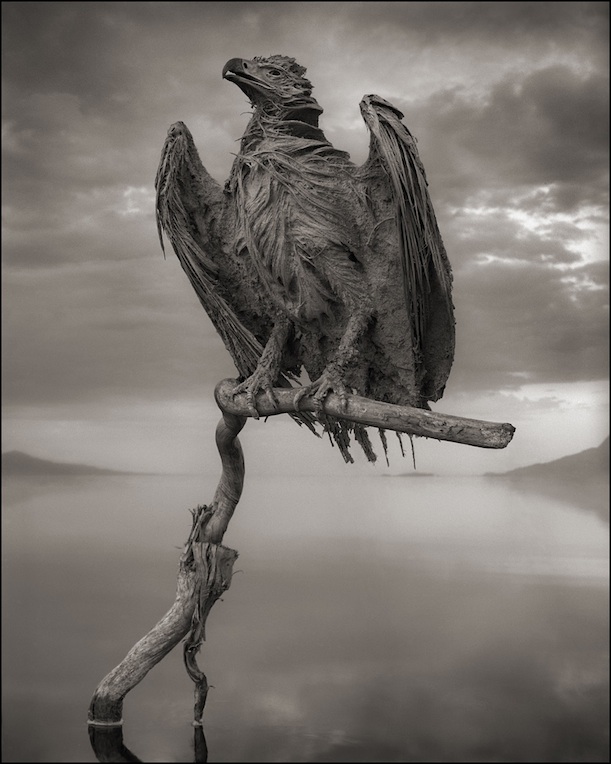

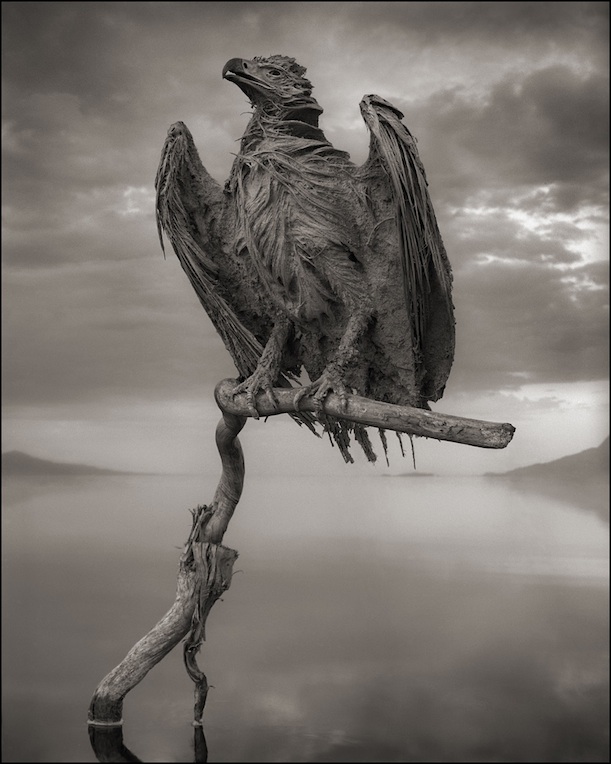

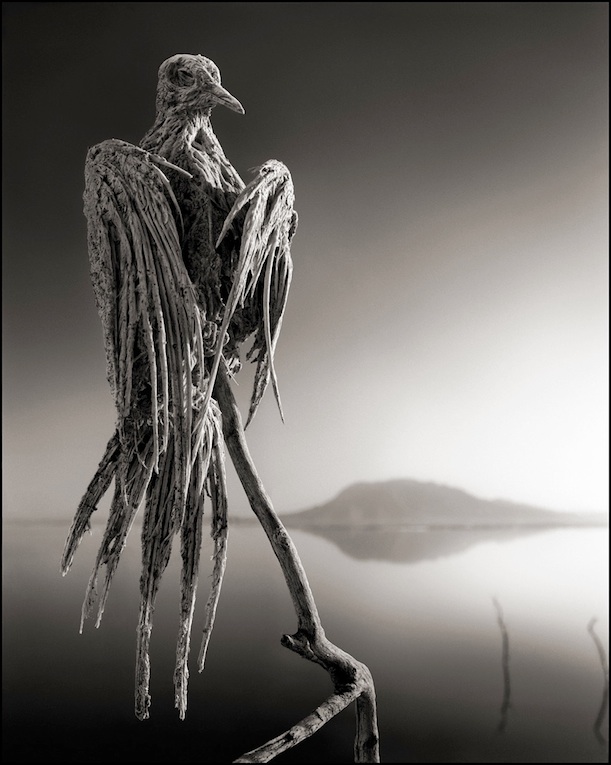

A calcified flamingo, preserved by the highly basic waters of Tanzania’s Lake Natron and photographed by Nick Brandt. ©

Nick Brandt 2013, Courtesy of Hasted Kraeutler Gallery, NY

In 2011, when he was traveling to shoot photos for a new book on the disappearing wildlife of East Africa,

Across the Ravaged Land, photographer

Nick Brandt came across a truly astounding place: A natural lake that seemingly turns all sorts of animals into stone.

“When I saw those creatures for the first time alongside the lake, I

was completely blown away,” says Brandt. “The idea for me, instantly,

was to take portraits of them as if they were alive.”

A bat ©

Nick Brandt 2013, Courtesy of Hasted Kraeutler Gallery, NY

The ghastly

Lake Natron, in northern Tanzania, is a

salt lake—meaning

that water flows in, but doesn’t flow out, so it can only escape by

evaporation. Over time, as water evaporates, it leaves behind high

concentrations of salt and other minerals, like at the Dead Sea and

Utah’s Great Salt Lake.

Unlike those other lakes, though, Lake Natron is extremely

alkaline, due to high amounts of the chemical

natron (a mix of sodium carbonate and baking soda) in the water. The water’s pH has been measured as high as 10.5—nearly

as high as ammonia. “It’s so high that it would strip the ink off my Kodak film boxes within a few seconds,” Brandt says.

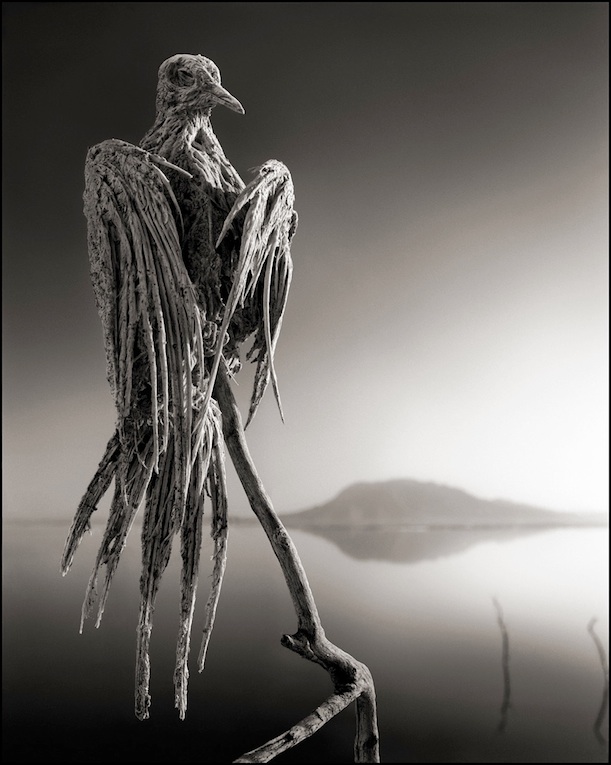

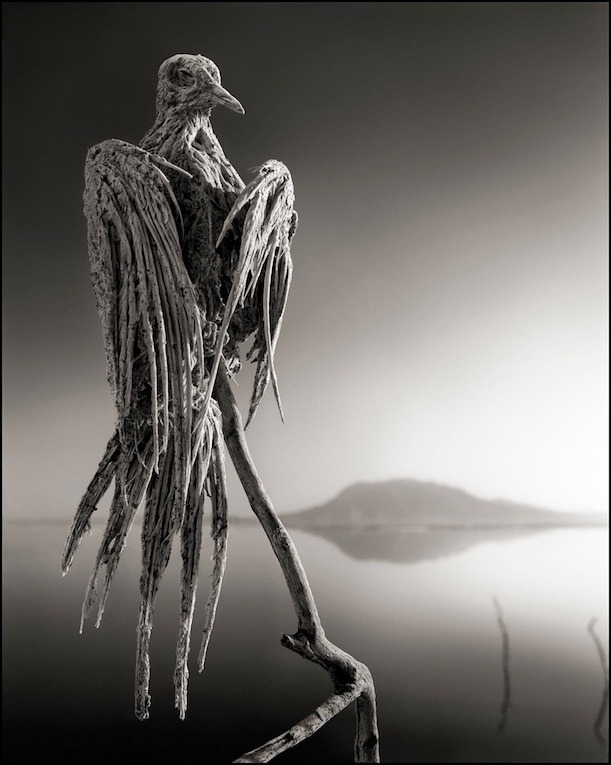

A swallow ©

Nick Brandt 2013, Courtesy of Hasted Kraeutler Gallery, NY

As you might expect, few creatures live in the harsh waters, which

can reach 140 degrees Fahreinheit—they’re home to just a single fish

species (

Alcolapia latilabris), some algae and a colony of flamingos that feeds on the algae and

breeds on the shore.

Frequently, though, migrating birds crash into the lake’s surface.

Brandt theorizes that the highly-reflective, chemical dense waters act

like a glass door, fooling birds into thinking they’re flying through

empty space (not long ago, a helicopter pilot tragically fell victim to

the same illusion, and his crashed aircraft was rapidly corroded by the

lake’s waters). During dry season, Brandt discovered, when the water

recedes, the birds’ desiccated, chemically-preserved carcasses wash up

along the coastline.

“It was amazing. I saw entire flocks of dead birds all washed ashore

together, lemming-like,” he says. “You’d literally get, say, a hundred

finches washed ashore in a 50-yard stretch.”

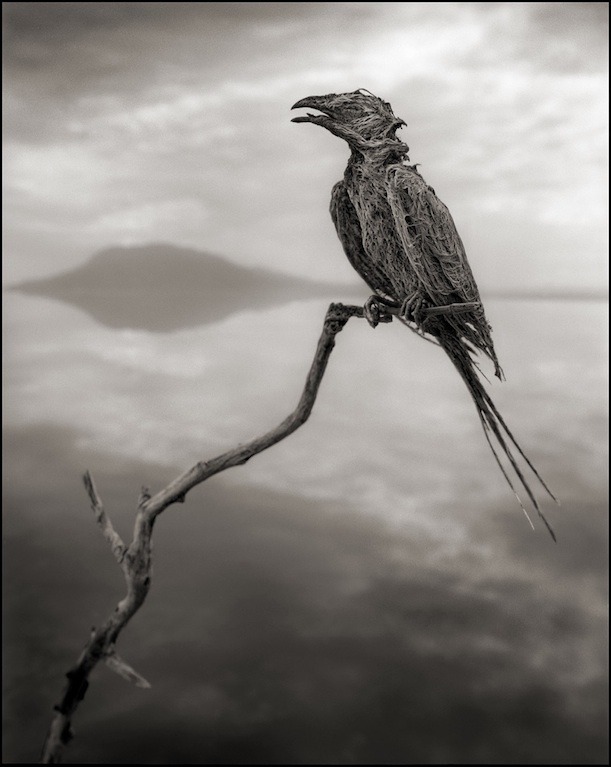

A songbird ©

Nick Brandt 2013, Courtesy of Hasted Kraeutler Gallery, NY

Over the course of about three weeks, Brandt worked with locals to

collect some of the most finely-preserved specimens. “They thought I was

absolutely insane—some crazy white guy, coming along offering money for

people to basically go on a treasure hunt around the lake for dead

birds,” he says. “When, one time, someone showed up with an entire,

well-preserved fish eagle, it was extraordinary.”

Just coming into contact with the water was dangerous. “It’s so

caustic, that even if you’ve got the tiniest cut, it’s very painful,” he

says. “Nobody would ever swim in this—it’d be complete madness.”

A fish eagle ©

Nick Brandt 2013, Courtesy of Hasted Kraeutler Gallery, NY

For the series of photos, titled “The Calcified” and featured in this month’s issue of

New Scientist, Brandt posed the carcasses in life-like positions. “But the bodies themselves are

exactly the

way the birds were found,” he insists. “All I did was position them on

the branches, feeding them through their stiff talons.”

A dove ©

Nick Brandt 2013, Courtesy of Hasted Kraeutler Gallery, NY

Lubbock, a city where churches outnumber tattoo parlors 25 to one, has some new billboards that combine the love of religion and ink. The billboards feature a hirsute Christ with words including "outcast," "jealous," and "faithless" tattooed on his body and outstretched arms.

Lubbock, a city where churches outnumber tattoo parlors 25 to one, has some new billboards that combine the love of religion and ink. The billboards feature a hirsute Christ with words including "outcast," "jealous," and "faithless" tattooed on his body and outstretched arms.