Zen and the Art of Fountain Pen Maintenance

(

Susan

M. Pigott is a fountain pen collector, pen and paperholic,

photographer, and professor. You can find more from Susan on her blog Scribalishess.)

Some fountain pen owners are fastidious about cleaning their fountain pens. They keep an ongoing record of which pens are inked, the date of inking, the color, when the pen needs to be cleaned, and the date the pen moved out of rotation. They typically have only a small number of pens inked at any given time. Then, each week or so, on an appointed day, they clean out their inked pens, dry them carefully, and choose a new set of pens to ink and use.

I am not one of those people.

I just spent an entire morning cleaning my fountain pen collection of about 70 pens. A few of these pens had been properly cleaned and stored, but, I am sad to say, most had been left with ink, unused, for months. I am a very naughty fountain pen owner. Honestly, it's not that I neglect my pens. I really do love them–all of them. I simply want to be able to use any given pen at a moment's notice as the mood calls for it. Plus, I'm disorganized and clutter-muddled and I can't keep track of which pens are inked and which are not. Thus, the Mega Pen Cleaning Morning involved the following sets of pens (I didn't take a photo of the first batch, so, really, there were five batches in all).

Now that all my pens are clean, I hope to do a better job of keeping track of them. To be sure, I have plenty of empty notebooks to do this. Special notebooks also exist for this purpose, such as the

InkJournal and Pen Habit's

"Currently Inked" log.

All of this made me think about the art of fountain pen maintenance, in particular cleaning.

Equipment

You really don't need much in terms of equipment to clean fountain pens. Here's what I use:

Water. I do all my cleaning at the kitchen sink using tap water. But some people prefer to use distilled water to avoid hard water deposits affecting their pens.

Pen flush. You can purchase commercial flush such as

Goulet's Pen Flush $11.00, or you can make your own. Basically Pen Flush is 1 part ammonia to 10 parts water and a couple of drops of Dawn Dish Detergent. If you use pen flush, draw it into the pen or converter, soak, and then rinse with plain water repeatedly to insure all the cleaning solution is gone.

Bulb Syringe. You can get one of these in the baby aisle of any supermarket. This is useful for cleaning out nib units.

Q-Tips. I use these only to wipe out and dry caps after I've rinsed them. I don't recommend using them on any other parts of your pens since fibers can get lodged in fountain pen barrels or nibs.

Towel. I just use paper towels, but you can use a dedicated soft towel for wiping down your pens. Paper towels are fine for letting your pens dry and wiping off nibs.

100% Pure Silicone Grease. If you have a sticky piston or converter, silicone grease is the answer. You can buy this from

Goulet $3.00 or, if you've purchased a TWSBI, you get a vial of it with the pen.

Toothpicks. I use these for dabbing silicone grease where it needs to go.

Methods

The way you clean a fountain pen depends on the type of pen you're working with. Some fountain pens are easier to clean than others. I will discuss the various methods I use with the fountain pens I own. I no longer own any vintage pens with sacs or complicated filling systems, so I will leave that for others to discuss.

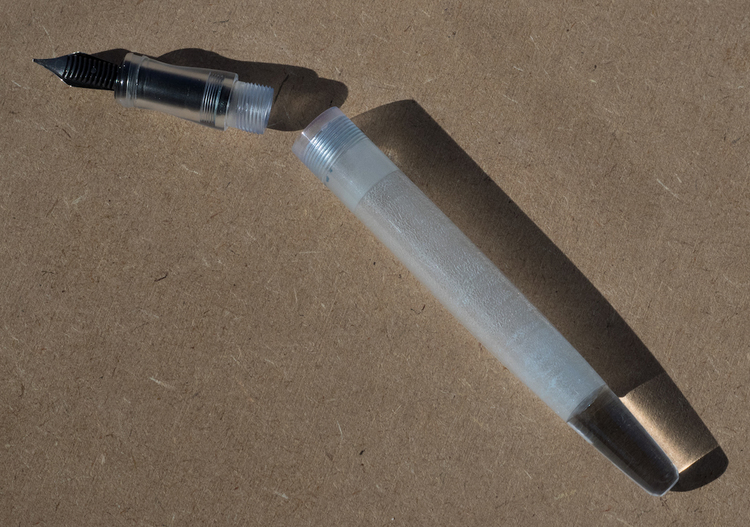

Eyedropper Fountain Pens

This is probably the easiest kind of fountain pen to clean. Just unscrew the nib, empty the ink, and rinse the barrel thoroughly. Put the nib unit under running, room-temperature tap water to rinse out the bulk of the ink. Then use the bulb syringe to gently finish cleansing the nib unit.

Squeeze gently (too much force and you might pop the nib off the feed. I've managed to do that). Repeat until the water is clear.

Cartridge/Converter Fountain Pens

The next easiest kind of pen to clean is cartridge/converter fountain pens. Empty the ink and separate the nib from the converter. Put the nib unit directly underneath running tap water to rinse out most of the ink, then finish with the bulb syringe.

The converter can be rinsed separately. Reassemble and you're done.

Piston Fountain Pens

Piston fountain pens are simple to operate, but getting all the ink out can be a chore. Turn the piston to empty out any remaining ink. Fill a bowl with water and insert the nib unit. Fill and empty until the water runs clear or your patience runs out. I flick the pen to empty out any remaining water, but be careful to hold onto your pen and watch where you flick–you don't want to mangle your nib on the side of the kitchen sink.

Vacuum Filler Fountain Pens

One of the most difficult kinds of pens to clean are Vacuum-filler fountain pens. It just seems that getting all the ink out requires an awful lot of plunging, but unless you can disassemble the pen (as you can with a Conid Bulkfiller), you simply have to rinse and repeat. Empty the ink out, pull out the plunger, put the nib unit in clean water, and plunge. I gently shake the pen to help remove the ink from the barrel walls. Empty and repeat until the water is as clear as you can get it.

Caps

Occasionally, ink leaks into pen caps, so I usually rinse out my caps when I'm cleaning my pens. Afterwards, I use a Q-Tip to wipe out any remaining ink and dry the pen cap. I leave the cap upright on a paper towel to complete the drying process.

Dealing with Sticky Pistons/Converters

Sometimes pistons get sticky and are difficult to move. If the fountain pen has a removable nib (as Pelikans do), the problem is easily remedied. Simply retract the piston, remove the nib unit, put a bit of silicone grease on a toothpick, and gently rub the grease onto the walls of the barrel as close to the piston seal as possible. You don't need much. Move the piston in and out to lubricate the pen and reinsert the nib unit.

Some converters (such as Platinum and Sailor) can also be disassembled and lubricated. I have to do this quite often with Platinum converters which get gummed up easily. Unscrew the gold/silver portion (getting it started can sometimes be difficult. Use rubber gloves if you need to get a better grip).

Pull out the piston assembly carefully. On Platinum converters, there's a tiny gasket that comes off and can easily be lost, so do this at a table or counter.

Dry off the end and smear a small amount of silicone grease on the portion that touches the converter sides. Reassemble and move the piston in and out until it works smoothly.

Obviously, there's a lot more to fountain pen maintenance than cleaning and lubricating pistons/converters. But this article provides a starting point.

How often you clean your pens is really up to you. You may decide on a rotation system as I described in the introduction. Or you may use your pens until the ink runs dry and clean them before refilling. Most modern fountain pen inks won't harm your fountain pens (but use extra caution with vintage pens). If you use highly saturated inks and/or iron gall inks, clean your pens more often.

Cleaning your fountain pens really can be an enjoyable, zen-like task. There's something quite satisfying about emptying a pen, flushing it clean, and readying it for a new color of ink.

Just don't wait to do your entire collection on one day.

Enjoy reading The Pen Addict? Then consider becoming a member to receive additional weekly content, giveaways, and discounts in The Pen Addict shop. Plus, you support me and the site directly, which I am very grateful for.

Membership starts at just $5/month, with a discounted annual option available. To find out more about membership

click here and join us!

Posted on July 1, 2016 by

Susan Pigott and filed under

Fountain Pen Maintenance.

23 Likes

Newer /

Older

Link:

http://www.penaddict.com/blog/2016/7/1/zen-and-the-art-of-fountain-pen-maintenance