Ante Scriptum: I wrote this post long ago, before even this

art-mirrors project formally commenced. It wasn’t even written about

mirrors per se, but to comment on another posting, about the

re-interpretations of the Diego Velázquez’

Meninas (you can find it here too, see

Contemplating reinterpretations).

When transferring it here, I decided not to edit it too much, and

leave as is, even though today I would write it differently.

To start, let’s have a look at the painting itself:

It’s a stunningly famous work of art, I bet it is in the top ten

most recognisable paintings in the world. As often happens in such

cases, it makes the task of writing about it both difficult and easy.

The easy part is that one shouldn’t really write about it at all, or at

least can skip the ‘basics’, and this knowledge about the years of

creation, the sizes, and plot, the heroes, and who are the maids, and

why the cap is read etc etc. In case you don’t know all that and really

want to, the

wikipedia is all yours.

The difficult part is, of course, related to the

tremendous popularity of this painting. This work is not just

over-researched, it’s hyper-over-research, the only bibliography of

‘serious’ publications about Las Meninas already comprises a relatively

large book. And it is hugely popular both among artists (and art

critics) and more theoretical folks, like historians and philosophers.

Michel Foucault in the first chapter of his

Les mots et les choses (1966)

made a claim that this is THE most important, pivotal work for the

European civilisation that reflects (sic!) the very formation of modern

identity, and modern way of thinking about and perceiving the world (and

us as a part of this world).

According to Foucault, Velázquez was the first who employed this

clever trick, of putting us, the viewers, into the place in front of

this painting in such a way that we inevitably understand that this is

the very position where the kind and the queen are standing. In this way

we are becoming the kind and the queen, and

theVelázquez-in-the-painting is actually painting us on his

canvas-in-the-painting.

Few years later this argument was support by

John Searle,

a renown American philosopher, who suggested that the painting

(re)presents, in a paradoxical way yet very accurate way, how we

perceive this world and at the same time what can be (re)presented by

art – see his paper

Las Meninas and the Paradox of Pictorial Representation (1980)

[

pdf].

However, Searle believes that if would be able to look at the

canvas-in-the-painting, we would see not the king and queen (or us), but

this very

Las Meninas! It is interesting how all these complex

debates can be distilled to a very simple issues, of what is actually

depicted on that canvas-in-the-painting.

The classical version (also endorsed by Foucault) says that what we see is a moment of sitting, of the Spanish king

Philip IV and his wife,

Mariana of Austria,

for their joint portrait, to be painted by Diego Velázquez, the court

painter. The session is interrupted by the visit of their daughter,

infanta

Margaret Theresa,

who entered the room with her entourage of the maids (=meninas). John

Searle obviously suggests a more paradoxical version, but still within a

framework of ‘pictorial representations’, as they call it in the

art-speak.

Few years later

Joel Snyder,

Professor of the Chicago University and a research of perception

(including of art), has published his critical response to the above

argument, in the paper titled

Las Meninas and the Mirror of the Prince (it

used to be online in full, but now I see only the first page). His

reply can be also called hyper-critical, as he basically levels to the

very ground all the arguments of Foucault-Searle (and to my taste in a

very mordant style; they try to avoid such style these days).

Basically, Snyder sees nothing ‘paradoxical’ in this painting (and in

general is against applying this term to art, suggesting instead to use

‘peculiar’ or simply ‘strange’). Some, but not all, drawings by Escher

are deliberately paradoxical, yet there is nothing ‘paradoxical’ about

Las Meninas.

There is no such things as the ‘placement of the viewer into the shoes

of the king’, alluded by Foucault or any other similar ‘games of

perception’.

According to Snyder, if we would carefully reconstruct the room in

its entirety, we would easily find a spot where we could stand and

observe this scene, of the painter making the portrait of the royal

couple. We are not the ‘king and queen’ here, but the visitors who

actually intruded the scene (and thus everybody looks at us with a

certain bewilderment.)

<tangent >

I always see all these perspective reconstructions of this painting

with a great deal of scepticism – if only because the original painting

was of very different size, unknown to us now. What we know is that it

was much bigger (wider), but it was damaged by the fire in a royal

palace, and this damaged part was simply cut off. Later it was also

moved from one room to another, and cut again, most likely from the

right size. Knowing that, all these contemporary reconstruction in

search of the magical ‘points of viewing’ are no more than wishful

thinking.

Above is one of the versions of the original painting constructed by Eve Sussman, who later also made a short movie (

89 Second in Alcazar)

reenacting this famous scene in the royal palace. Sussman also assumes

that the painting was much larger (the red square is what we have left

today).

However, this reconstruction is no better – or worse – that any

others, and without the exact data on the original sizes any theoretical

constructions remain to be sortilege of a kind.

</tangent >

But Synder went even further, acting now not so much as a researcher

of perception, but a researcher of (art) history. He actually argues

that Velázquez-in-the-painting paints nothing, i.e., there was no

‘portrait’ of the king and queen intended. What he is making is yet

another portrait of the young infanta, commissioned by the king, and as

with any other portraits of her, before and after that, he is loading it

with a certain

morality.

In this case, Velázquez is exploiting a certain play of words (and meaning) which Snyders analyses in details.

Let’s take the front page of the book that was very well-known back then in Spain, so called

Idea de un principe politico cristiano, by some Diego de Saavedra Fajardo. We see that instead of canvas it depicts a mirror.

The issue is that another, better known title of this boos was ‘

The Mirror of the Christian Politician (Ruler)‘,

whereby the word ‘mirror’ was used with a meaning of a ‘codex’ or a

‘corpus (of laws)’. This was not that only book of such sort, of course.

In fact, there was a large assortment of various ‘mirrors’ at that

time, such as ‘The Mirror of a True Gentleman’ or ‘The Mirror of

Respectable Husband’ and so on.

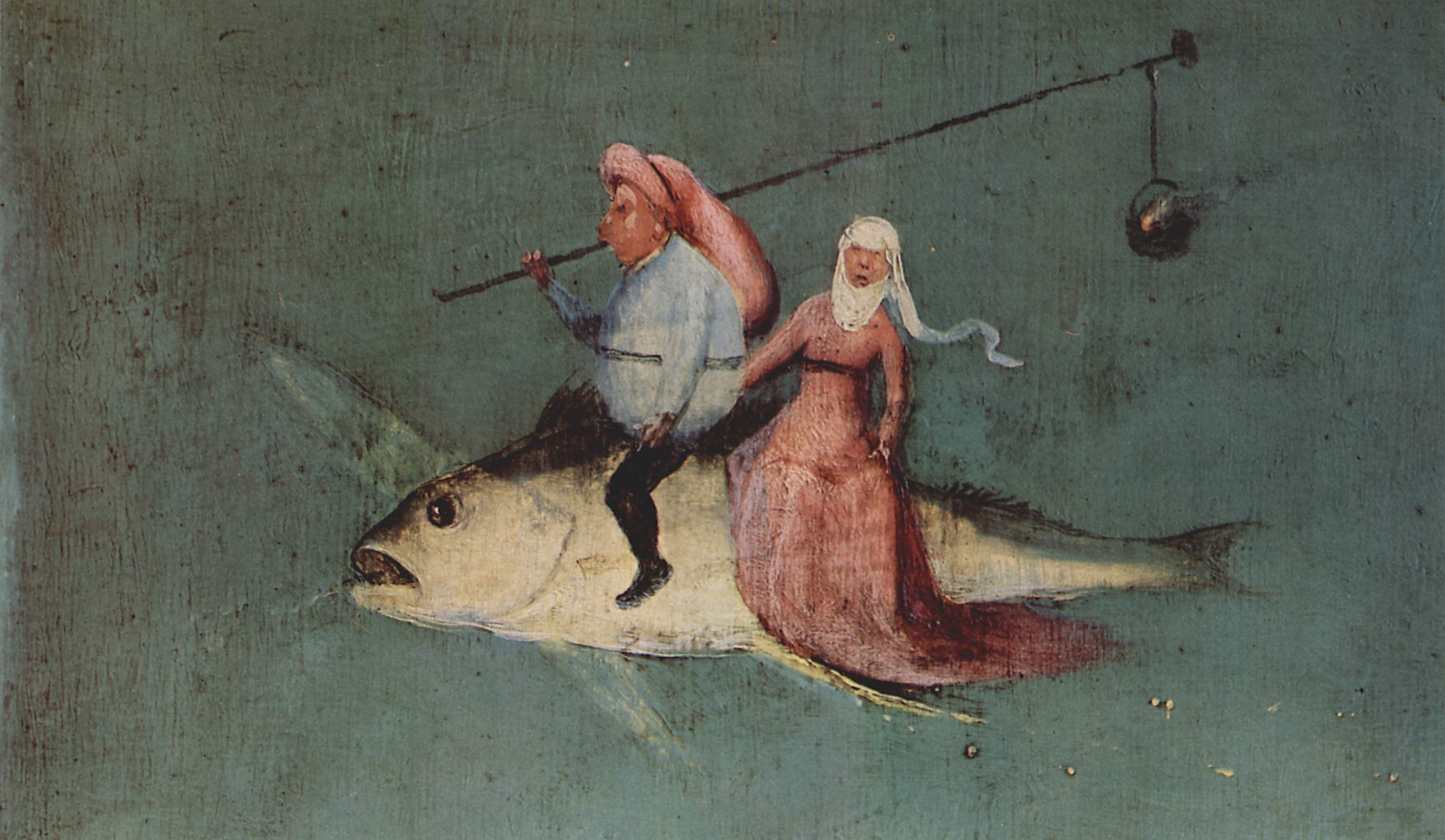

Below, for example, is a front page of the‘The Mariner’s Mirror’ (1588) written by

Lucas Jansz Waghenaer, famous Flemish explorer and cartographer.

Basically, Snyder argues that the ‘mirror’ we see on the painting is

not more than an allusion to this meaning of the word, and thus the

purpose of the work was to depict the infant with a mirror, in other

words, with the admonishment of the king to his daughter.

Velázquez panted numerous portraits of the infanta, depicting her

different ages (and I compiled only a few of them in the collage I

started this posting with). Many of them indeed have similar symbolic

messages. For instance, the fan on the left painting below signified a

certain age (and the status) she reached, after which she had to point

to the objects only by such fan, not by hand. The painting with the

globe shown on a background of another portrait was to signal the start

of more serious studies she had to go through (but of course also

manifested the vase Spanish possessions of land in Latin America).

|

|

This last portrait is also an example of another theme, of motif of

the Velázquez’ oeuvre, namely ‘Painting in the painting’. I think it’s a

very important element of his art, and largely unnoticed (or at least I

never read any detailed analysis of this topic). To comment on this,

albeit very briefly, I have to start from his earlier works (per se

having nothing to do with the mirrors).

Below is a typical work of early Velázquez, made in the so called

bodegón genre

(from

Spanish ‘bodega’, a tavern or a wine cellar); appropriately, it depicts

lots of food stuff and kitchen utensils (the official title of the

painting is ‘

Old Woman Frying Eggs‘, 1618):

He made a number of such works, and they were all of good quality,

but also were not able to bring neither fame nor income; the latter two

were given for either religious work or portraits of nobility. I think

Velázquez found an interesting bridge between these worlds and the

subjects more familiar to him.

Here is also one of his earlier paintings, so called

Christ in the House of Mary and Martha (c.1620):

At the first look, this is a very simple illustration of the famous

story from the Bible, about pragmatic Martha and devotional Mary (not

the Saint Mary, though). Yet the painting contains a puzzle, of what is

actually depicted in its upper left corner. Is it a painting? a door?

or, perhaps, a mirror?

But before even answering this question, the very depiction of the

figure of Christ was transferring this otherwise simple bodegon into a

symbolic art-work, thus also elevating its author on a higher

professional level (or so I think).

The latter version, about mirror, is very unlikely, of course,

because the mirrors of such size were very rare and VERY expensive back

then (and under ‘back then’ I mean the times of Velázquez, not Jesus

Christ). One wouldn’t expect to see in the house of modestly living

family of Martha and Mary.

Interestingly, though, this version was quite popular at some point,

partly because the conditions of the painting. It was getting darker

with time, but the restoration efforts mostly meant cleaning certain

areas by saliva, so with time the area with Christ became the brightest

spot, while the frame turned to be into one dark area.

When the painting was restored, it became obvious that depicted is

the painting on a wall. However, as a more careful analysis with the use

of X-rays revealed, Velázquez perhaps intended to make it a ‘door’; the

lower part of frame appeared much later during the process.

Either way, what we see here is a trick employed by some painters,

namely depicting a picture inside a painting. Velázquez used the same

trick in another work of about same time,

Kitchen Maid with the Supper at Emmaus (с. 1620)

Soon after Velázquez will travel to Madrid, and soon propelled into

the court painter. His tremendously quick take-off is mostly due to his

talents and skills, of course, but also the result of multiple

serendipitous circumstances (right-time-right-place kind of things; he

came to Madrid in March 1622, and in December of this year the previous

court’s painter suddenly died, being relatively young by then.)

He painted a portrait of his first patron in Madrid, Don Juan de

Fonseca, who liked it, and who showed to the king. A portrait of the

king was commissioned, and was completed basically within one day, after

just one sitting, in August 1623. Apparently, Philip liked it so much

that he ordered to withdraw from circulation all the previous painting

of him and granted to DiegoVelázquez and exclusive right to paint the

king, together with a position of the new court painter, the position he

officially took from 1624. In less than two years Velázquez made a

journey from an unknown master to the painter of the mightiest

monarch of that time, simples.

Velázquez will paint numerous portraits of the king, and later his

family, as well as portraits of nobility. His style will be gradually

becoming more gentle, compared to the stiff and sober manner of his

earlier works, and also inevitably more pompous (though he will never

reach the grandiosity of Rubens, very fortunately). Interestingly, but

he met Rubens who came to Madrid in 1928, at the peak of his fame,

though the latter didn’t have much influence on still quite young Diego

Velázquez.

Rubens, however, has made on the fate of the Spanish court painter,

as it was most likely him who finally persuaded Velázquez to travel to

Italy, to learn about, and from Italian art. Diego Velázquez spent

almost a year and a half in Italy, and came back to Spain a very

different painter; art historian often divided his works on two periods,

‘Before Italy’ and ‘After Italy’.

One major difference is a much better understanding of human anatomy,

that Velázquez could learn both from the famous works of art but also

from the real (nude) models, the opportunity he was obviously lacking in

still very dogmatic Spain. If before his human figures were more like

‘walking costumes’, now he could paint human body in an accurate, thus

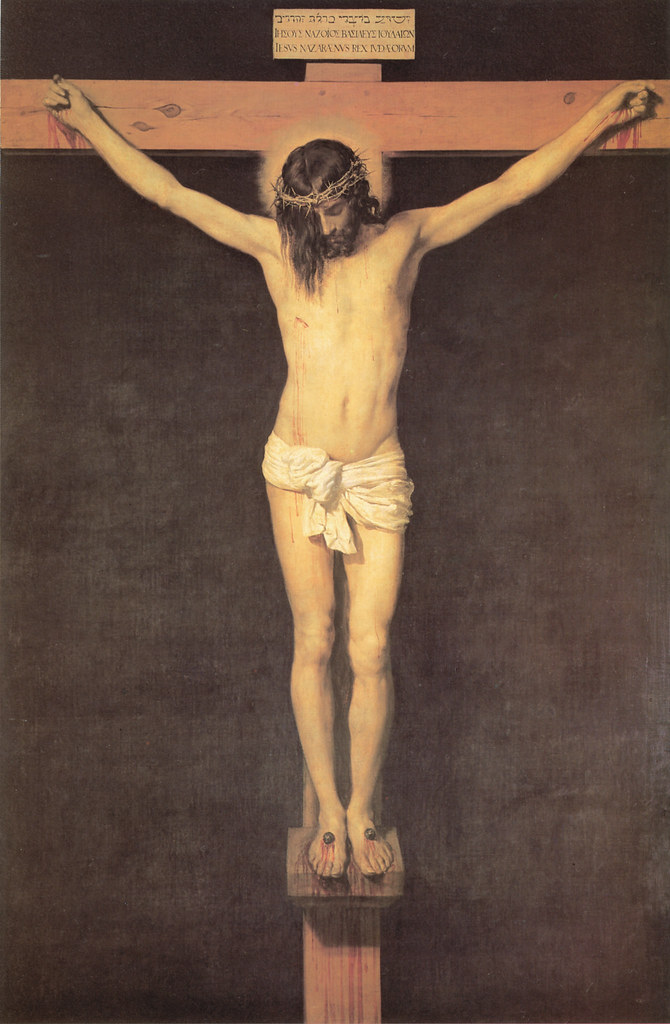

very powerful way – just look at his Christ on the Cross (1632), a giant

and almost hyper-realistic work, currently in Prado Museum.

His portraits are becoming more and more powerful too; interestingly,

though, but we don’t see the return of his painting-in-painting ‘trick’

for many years. It will appear again only after his second trip to

Italy, where he as again sent in 1649.

This time it’s not so much to learn but to show his own style and

also collect famous works of art for the Spanish royal collection he was

also curating. It was during this trip he would paint now famous

portrait of Pope Innocent X (again, basically after one sitting):

However, for me his second trip to Italy is mostly interesting

because it resulted in his first mirror-in-art – and also his only nude,

the famous

Venus del espejo – which is, by the way, also an example of painting-in-painting:

There are relatively detailed life records describing many works

of Velázquez – when any particular was started, who commissioned it and

how much was paid etc; besides being a painter, Velázquez was also in

charge of certain court property (the paintings and other art work, but

also furniture, valuable tableware, and so one, and kept detailed

records of these items).

A bit suspiciously, therefore, that there no records related to this

work, and we even don’t know who is depicted here. That inevitably

resulted in speculations that she was not just a ‘model, but a mistress

of the painter in Italy. There are also no data on the actual process of

painting, i.e., whether it was a real sitting or a work created from

memory.

This later aspect is important, because Velázquez – similar to many

other painters depicting mirrors – made a typical mistake, known as the

Venus Effect (the

article about this subject on wikipedia is illustrated by this very

painting, though historically speaking it was Titian who made the first

‘wrong’ Venus with mirror).

In essence, if it would be a real scene, we wouldn’t be able to see

the face of the woman – or, rather, if we see the face, it means that

she is not able to see herself in this mirror. Which in turn means that

the cupid is not there to show to the goddess her beauty, but to aid her

to play the (visual) tricks with us.

Speaking about modernity, and perception of art, Foucault should have better used this painting, not

Meninas,

for his far-fetching conclusions, because it does represent a very

clever inter-play with the viewer, including his ‘placement’ into a

certain position (if not physical, then social).

The history of the work is quite perplex (I told that the date of its

conception is unknown, but neither is neither is the date of finish –

according to one version,Velázquez brought it back from Italy to Spain

deliberately unfinished, to avoid and conflicts with the church

authorities. In any case, the work was eventually completed, and was in

the royal collection until the beginning of the 19th century, when it

was brought to England, to the so called Rokeby Park, which also lead to

another name for the painting, the

Rokeby Venus.

Later in 1656 Velázquez will create his Meninas (see above the

debates about this work, to which I only wanted to add this one

dimension, of a painting-in-painting aspect).

Shortly before his death in 1660 Velázquez will create another

beautiful and very enigmatic work, yet another example

of painting-in-painting – though this time he even exceeded himself,

creating the third layer, so it is painting-in-painting-in-painting:

The work is called

Arachne (1659), and depicts a group of the weaving women (although also an allusion to the Greek mythological figure of

Arachne

who challenged Athena, lost and was transformed into a spider). As a

backdrop of this scene the painter used another painting, which in turn

depict a tapestry.

As a way of conclusion

When I write ‘actually’ or ‘in fact’ in relation to the content of

the painting, I am actually not in search of any final truth or the

real-real version. I think my motivation is to multiply rather than

reduce meanings; the more the merrier kind of logic. I don’t really

consider Foucault ‘wrong’, or Snyder ‘right’ in their debates about

Meninas. They

all certain valid points, and thus right to exist, but what I really

like is when these multiple viewpoints also lead to the emergence of

even more complex frameworks and considerations (and

evenconsiderations-in-considerations).

Basically, that’s why I even started not from the work itself, but

from its various re-interpretations and remakes, and then

reinterpretations of reinterpretations, as in the case of David

Hamilton’s recycling of Picasso’s version of

Meninas.

By the way, the vase majority of these

re-interpretations that I gathered

point that the mirror was one of the least interesting object for the

authors. It is there, most often, but the key focusing triangle is

invariably The Girl – Her Skirt – and The Dog.

One of my favorite remakes is the version by Martín La Spina, called

Meninas detras del espejo

(Meninas behind a mirror) (2004) where in the mirror we see the

very Velázquez. I think he deserved this place more than anybody else.

Daniela Macorin

Daniela Macorin