Monday, March 25, 2013

Neorphilia can be an indicator of well-being

Take the test.......

Are you a neophiliac?

Do you make decisions quickly based on incomplete information?

Do you lose your temper quickly?

Are you easily bored?

Do you thrive in conditions that seem chaotic to others, or do you like everything well organized?

Those are the kinds of questions used to measure novelty-seeking, a personality trait long associated with trouble.

As researchers analyzed its genetic roots and relations to the brain’s dopamine system, they linked this trait with problems like attention deficit disorder, compulsive spending and gambling, alcoholism, drug abuse and criminal behavior.

Now, though, after extensively tracking novelty-seekers, researchers are seeing the upside.

In the right combination with other traits, it’s a crucial predictor of well-being.

“Novelty-seeking is one of the traits that keeps you healthy and happy and fosters personality growth as you age,” says C. Robert Cloninger, the psychiatrist who developed personality tests for measuring this trait.

The problems with novelty-seeking showed up in his early research in the 1990s; the advantages have become apparent after he and his colleagues tested and tracked thousands of people in the United States, Israel and Finland.

“It can lead to antisocial behavior,” he says, “but if you combine this adventurousness and curiosity with persistence and a sense that it’s not all about you, then you get the kind of creativity that benefits society as a whole.”

Fans of this trait are calling it “neophilia” and pointing to genetic evidence of its importance as humans migrated throughout the world.

In her survey of the recent research, “New: Understanding Our Need for Novelty and Change,” the journalist Winifred Gallagher argues that neophilia has always been the quintessential human survival skill, whether adapting to climate change on the ancestral African savanna or coping with the latest digital toy from Silicon Valley.

“Nothing reveals your personality more succinctly than your characteristic emotional reaction to novelty and change over time and across many situations,” Ms. Gallagher says.

“It’s also the most important behavioral difference among individuals.” Drawing on the work of Dr. Cloninger and other personality researchers, she classifies people as neophobes, neophiles and, at the most extreme, neophiliacs. (To classify yourself, you can take a quiz on the Well blog.)

“Although we’re a neophilic species,” Ms. Gallagher says, “as individuals we differ in our reactions to novelty, because a population’s survival is enhanced by some adventurers who explore for new resources and worriers who are attuned to the risks involved.”

The adventurous neophiliacs are more likely to possess a “migration gene,” a DNA mutation that occurred about 50,000 years ago, as humans were dispersing from Africa around the world, according to Robert Moyzis, a biochemist at the University of California, Irvine. The mutations are more prevalent in the most far-flung populations, like Indian tribes in South America descended from the neophiliacs who crossed the Bering Strait.

These genetic variations affect the brain’s regulation of dopamine, the neurotransmitter associated with the processing of rewards and new stimuli (and drugs like cocaine).

The variations have been linked to faster reaction times, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and a higher penchant for novelty-seeking and risk-taking.

But genes, as usual, are only part of the story. Researchers have found that people’s tendency for novelty-seeking also depends on their upbringing, on the local culture and on their stage of life. By some estimates, the urge for novelty drops by half between the ages of 20 and 60.

Dr. Cloninger, a professor of psychiatry and genetics at Washington University in St. Louis, tracked people using a personality test he developed two decades ago, the Temperament and Character Inventory.

By administering the test periodically and chronicling changes in people’s lives over more than a decade, he and colleagues looked for the crucial combination of traits in people who flourished over the years — the ones who reported the best health, most friends, fewest emotional problems and greatest satisfaction with life.

What was the secret to their happy temperament and character?

A trio of traits.

They scored high in novelty-seeking as well in persistence and “self-transcendence.”

Persistence, the stick-to-it virtue promoted by strong-willed Victorians, may sound like the opposite of novelty-seeking, but the two traits can coexist and balance each other.

“People with persistence tend to be achievers because they’ll keep working at something even when there’s no immediate reward,” Dr. Cloninger says.

“They’ll think, ‘I didn’t win this time, but next time I will.’ But what if conditions have changed? Then you’re better off trying something new.

To succeed, you want to be able to regulate your impulses while also having the imagination to see what the future would be like if you tried something new.”

The other trait in the trio, self-transcendence, gives people a larger perspective.

“It’s the capacity to get lost in the moment doing what you love to do, to feel a connection to nature and humanity and the universe,” Dr. Cloninger says.

“It’s sometimes found in disorganized people who are immature and do a lot of wishful thinking and daydreaming, but when it’s combined with persistence and novelty-seeking, it leads to personal growth and enables you to balance your needs with those of the people around you.”

In some ways, this is the best of all possible worlds for novelty seekers. Never have there so many new things to sample, especially in the United States, a nation of immigrants, which Ms. Gallagher ranks as the most neophilic society in history.

In pre-industrial cultures, curiosity was sometimes considered a vice, and people didn’t expect constant stimulation. The English word “boredom” didn’t come into popular use until the 19th century.

Today, it’s the ultimate insult — borrrring — among teenagers perpetually scanning screens for something new.

Their neophilia may be an essential skill, just as it was for hunter-gatherers evolving on the savanna, but it can also be problematic.

The urge for novelty, like the primal urge to consume fat, can lead you astray.

“We now consume about 100,000 words each day from various media, which is a whopping 350 percent increase, measured in bytes, over what we handled back in 1980,” Ms. Gallagher says.

“Neophilia spurs us to adjust and explore and create technology and art, but at the extreme it can fuel a chronic restlessness and distraction.”

She and Dr. Cloninger both advise neophiles to be selective in their targets.

“Don’t go wide and shallow into useless trivia,” Ms. Gallagher says.

“Use your neophilia to go deep into subjects that are important to you.”

That’s a traditional bit of advice, but to some dopamine-charged neophiliacs, it may qualify as news.

Are you a neophiliac?

Do you make decisions quickly based on incomplete information?

Do you lose your temper quickly?

Are you easily bored?

Do you thrive in conditions that seem chaotic to others, or do you like everything well organized?

Those are the kinds of questions used to measure novelty-seeking, a personality trait long associated with trouble.

As researchers analyzed its genetic roots and relations to the brain’s dopamine system, they linked this trait with problems like attention deficit disorder, compulsive spending and gambling, alcoholism, drug abuse and criminal behavior.

Now, though, after extensively tracking novelty-seekers, researchers are seeing the upside.

In the right combination with other traits, it’s a crucial predictor of well-being.

“Novelty-seeking is one of the traits that keeps you healthy and happy and fosters personality growth as you age,” says C. Robert Cloninger, the psychiatrist who developed personality tests for measuring this trait.

The problems with novelty-seeking showed up in his early research in the 1990s; the advantages have become apparent after he and his colleagues tested and tracked thousands of people in the United States, Israel and Finland.

“It can lead to antisocial behavior,” he says, “but if you combine this adventurousness and curiosity with persistence and a sense that it’s not all about you, then you get the kind of creativity that benefits society as a whole.”

Fans of this trait are calling it “neophilia” and pointing to genetic evidence of its importance as humans migrated throughout the world.

In her survey of the recent research, “New: Understanding Our Need for Novelty and Change,” the journalist Winifred Gallagher argues that neophilia has always been the quintessential human survival skill, whether adapting to climate change on the ancestral African savanna or coping with the latest digital toy from Silicon Valley.

“Nothing reveals your personality more succinctly than your characteristic emotional reaction to novelty and change over time and across many situations,” Ms. Gallagher says.

“It’s also the most important behavioral difference among individuals.” Drawing on the work of Dr. Cloninger and other personality researchers, she classifies people as neophobes, neophiles and, at the most extreme, neophiliacs. (To classify yourself, you can take a quiz on the Well blog.)

“Although we’re a neophilic species,” Ms. Gallagher says, “as individuals we differ in our reactions to novelty, because a population’s survival is enhanced by some adventurers who explore for new resources and worriers who are attuned to the risks involved.”

The adventurous neophiliacs are more likely to possess a “migration gene,” a DNA mutation that occurred about 50,000 years ago, as humans were dispersing from Africa around the world, according to Robert Moyzis, a biochemist at the University of California, Irvine. The mutations are more prevalent in the most far-flung populations, like Indian tribes in South America descended from the neophiliacs who crossed the Bering Strait.

These genetic variations affect the brain’s regulation of dopamine, the neurotransmitter associated with the processing of rewards and new stimuli (and drugs like cocaine).

The variations have been linked to faster reaction times, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and a higher penchant for novelty-seeking and risk-taking.

But genes, as usual, are only part of the story. Researchers have found that people’s tendency for novelty-seeking also depends on their upbringing, on the local culture and on their stage of life. By some estimates, the urge for novelty drops by half between the ages of 20 and 60.

Dr. Cloninger, a professor of psychiatry and genetics at Washington University in St. Louis, tracked people using a personality test he developed two decades ago, the Temperament and Character Inventory.

By administering the test periodically and chronicling changes in people’s lives over more than a decade, he and colleagues looked for the crucial combination of traits in people who flourished over the years — the ones who reported the best health, most friends, fewest emotional problems and greatest satisfaction with life.

What was the secret to their happy temperament and character?

A trio of traits.

They scored high in novelty-seeking as well in persistence and “self-transcendence.”

Persistence, the stick-to-it virtue promoted by strong-willed Victorians, may sound like the opposite of novelty-seeking, but the two traits can coexist and balance each other.

“People with persistence tend to be achievers because they’ll keep working at something even when there’s no immediate reward,” Dr. Cloninger says.

“They’ll think, ‘I didn’t win this time, but next time I will.’ But what if conditions have changed? Then you’re better off trying something new.

To succeed, you want to be able to regulate your impulses while also having the imagination to see what the future would be like if you tried something new.”

The other trait in the trio, self-transcendence, gives people a larger perspective.

“It’s the capacity to get lost in the moment doing what you love to do, to feel a connection to nature and humanity and the universe,” Dr. Cloninger says.

“It’s sometimes found in disorganized people who are immature and do a lot of wishful thinking and daydreaming, but when it’s combined with persistence and novelty-seeking, it leads to personal growth and enables you to balance your needs with those of the people around you.”

In some ways, this is the best of all possible worlds for novelty seekers. Never have there so many new things to sample, especially in the United States, a nation of immigrants, which Ms. Gallagher ranks as the most neophilic society in history.

In pre-industrial cultures, curiosity was sometimes considered a vice, and people didn’t expect constant stimulation. The English word “boredom” didn’t come into popular use until the 19th century.

Today, it’s the ultimate insult — borrrring — among teenagers perpetually scanning screens for something new.

Their neophilia may be an essential skill, just as it was for hunter-gatherers evolving on the savanna, but it can also be problematic.

The urge for novelty, like the primal urge to consume fat, can lead you astray.

“We now consume about 100,000 words each day from various media, which is a whopping 350 percent increase, measured in bytes, over what we handled back in 1980,” Ms. Gallagher says.

“Neophilia spurs us to adjust and explore and create technology and art, but at the extreme it can fuel a chronic restlessness and distraction.”

She and Dr. Cloninger both advise neophiles to be selective in their targets.

“Don’t go wide and shallow into useless trivia,” Ms. Gallagher says.

“Use your neophilia to go deep into subjects that are important to you.”

That’s a traditional bit of advice, but to some dopamine-charged neophiliacs, it may qualify as news.

Are you a neophiliac?

Do you make decisions quickly based on incomplete information?

Do you lose your temper quickly?

Are you easily bored?

Do you thrive in conditions that seem chaotic to others, or do you like everything well organized?

Those are the kinds of questions used to measure novelty-seeking, a personality trait long associated with trouble.

As researchers analyzed its genetic roots and relations to the brain’s dopamine system, they linked this trait with problems like attention deficit disorder, compulsive spending and gambling, alcoholism, drug abuse and criminal behavior.

Now, though, after extensively tracking novelty-seekers, researchers are seeing the upside.

In the right combination with other traits, it’s a crucial predictor of well-being.

“Novelty-seeking is one of the traits that keeps you healthy and happy and fosters personality growth as you age,” says C. Robert Cloninger, the psychiatrist who developed personality tests for measuring this trait.

The problems with novelty-seeking showed up in his early research in the 1990s; the advantages have become apparent after he and his colleagues tested and tracked thousands of people in the United States, Israel and Finland.

“It can lead to antisocial behavior,” he says, “but if you combine this adventurousness and curiosity with persistence and a sense that it’s not all about you, then you get the kind of creativity that benefits society as a whole.”

Fans of this trait are calling it “neophilia” and pointing to genetic evidence of its importance as humans migrated throughout the world.

In her survey of the recent research, “New: Understanding Our Need for Novelty and Change,” the journalist Winifred Gallagher argues that neophilia has always been the quintessential human survival skill, whether adapting to climate change on the ancestral African savanna or coping with the latest digital toy from Silicon Valley.

“Nothing reveals your personality more succinctly than your characteristic emotional reaction to novelty and change over time and across many situations,” Ms. Gallagher says.

“It’s also the most important behavioral difference among individuals.” Drawing on the work of Dr. Cloninger and other personality researchers, she classifies people as neophobes, neophiles and, at the most extreme, neophiliacs. (To classify yourself, you can take a quiz on the Well blog.)

“Although we’re a neophilic species,” Ms. Gallagher says, “as individuals we differ in our reactions to novelty, because a population’s survival is enhanced by some adventurers who explore for new resources and worriers who are attuned to the risks involved.”

The adventurous neophiliacs are more likely to possess a “migration gene,” a DNA mutation that occurred about 50,000 years ago, as humans were dispersing from Africa around the world, according to Robert Moyzis, a biochemist at the University of California, Irvine. The mutations are more prevalent in the most far-flung populations, like Indian tribes in South America descended from the neophiliacs who crossed the Bering Strait.

These genetic variations affect the brain’s regulation of dopamine, the neurotransmitter associated with the processing of rewards and new stimuli (and drugs like cocaine).

The variations have been linked to faster reaction times, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and a higher penchant for novelty-seeking and risk-taking.

But genes, as usual, are only part of the story. Researchers have found that people’s tendency for novelty-seeking also depends on their upbringing, on the local culture and on their stage of life. By some estimates, the urge for novelty drops by half between the ages of 20 and 60.

Dr. Cloninger, a professor of psychiatry and genetics at Washington University in St. Louis, tracked people using a personality test he developed two decades ago, the Temperament and Character Inventory.

By administering the test periodically and chronicling changes in people’s lives over more than a decade, he and colleagues looked for the crucial combination of traits in people who flourished over the years — the ones who reported the best health, most friends, fewest emotional problems and greatest satisfaction with life.

What was the secret to their happy temperament and character?

A trio of traits.

They scored high in novelty-seeking as well in persistence and “self-transcendence.”

Persistence, the stick-to-it virtue promoted by strong-willed Victorians, may sound like the opposite of novelty-seeking, but the two traits can coexist and balance each other.

“People with persistence tend to be achievers because they’ll keep working at something even when there’s no immediate reward,” Dr. Cloninger says.

“They’ll think, ‘I didn’t win this time, but next time I will.’ But what if conditions have changed? Then you’re better off trying something new.

To succeed, you want to be able to regulate your impulses while also having the imagination to see what the future would be like if you tried something new.”

The other trait in the trio, self-transcendence, gives people a larger perspective.

“It’s the capacity to get lost in the moment doing what you love to do, to feel a connection to nature and humanity and the universe,” Dr. Cloninger says.

“It’s sometimes found in disorganized people who are immature and do a lot of wishful thinking and daydreaming, but when it’s combined with persistence and novelty-seeking, it leads to personal growth and enables you to balance your needs with those of the people around you.”

In some ways, this is the best of all possible worlds for novelty seekers. Never have there so many new things to sample, especially in the United States, a nation of immigrants, which Ms. Gallagher ranks as the most neophilic society in history.

In pre-industrial cultures, curiosity was sometimes considered a vice, and people didn’t expect constant stimulation. The English word “boredom” didn’t come into popular use until the 19th century.

Today, it’s the ultimate insult — borrrring — among teenagers perpetually scanning screens for something new.

Their neophilia may be an essential skill, just as it was for hunter-gatherers evolving on the savanna, but it can also be problematic.

The urge for novelty, like the primal urge to consume fat, can lead you astray.

“We now consume about 100,000 words each day from various media, which is a whopping 350 percent increase, measured in bytes, over what we handled back in 1980,” Ms. Gallagher says.

“Neophilia spurs us to adjust and explore and create technology and art, but at the extreme it can fuel a chronic restlessness and distraction.”

She and Dr. Cloninger both advise neophiles to be selective in their targets.

“Don’t go wide and shallow into useless trivia,” Ms. Gallagher says.

“Use your neophilia to go deep into subjects that are important to you.”

That’s a traditional bit of advice, but to some dopamine-charged neophiliacs, it may qualify as news.

Are you a neophiliac?

Do you make decisions quickly based on incomplete information?

Do you lose your temper quickly?

Are you easily bored?

Do you thrive in conditions that seem chaotic to others, or do you like everything well organized?

Those are the kinds of questions used to measure novelty-seeking, a personality trait long associated with trouble.

As researchers analyzed its genetic roots and relations to the brain’s dopamine system, they linked this trait with problems like attention deficit disorder, compulsive spending and gambling, alcoholism, drug abuse and criminal behavior.

Now, though, after extensively tracking novelty-seekers, researchers are seeing the upside.

In the right combination with other traits, it’s a crucial predictor of well-being.

“Novelty-seeking is one of the traits that keeps you healthy and happy and fosters personality growth as you age,” says C. Robert Cloninger, the psychiatrist who developed personality tests for measuring this trait.

The problems with novelty-seeking showed up in his early research in the 1990s; the advantages have become apparent after he and his colleagues tested and tracked thousands of people in the United States, Israel and Finland.

“It can lead to antisocial behavior,” he says, “but if you combine this adventurousness and curiosity with persistence and a sense that it’s not all about you, then you get the kind of creativity that benefits society as a whole.”

Fans of this trait are calling it “neophilia” and pointing to genetic evidence of its importance as humans migrated throughout the world.

In her survey of the recent research, “New: Understanding Our Need for Novelty and Change,” the journalist Winifred Gallagher argues that neophilia has always been the quintessential human survival skill, whether adapting to climate change on the ancestral African savanna or coping with the latest digital toy from Silicon Valley.

“Nothing reveals your personality more succinctly than your characteristic emotional reaction to novelty and change over time and across many situations,” Ms. Gallagher says.

“It’s also the most important behavioral difference among individuals.” Drawing on the work of Dr. Cloninger and other personality researchers, she classifies people as neophobes, neophiles and, at the most extreme, neophiliacs. (To classify yourself, you can take a quiz on the Well blog.)

“Although we’re a neophilic species,” Ms. Gallagher says, “as individuals we differ in our reactions to novelty, because a population’s survival is enhanced by some adventurers who explore for new resources and worriers who are attuned to the risks involved.”

The adventurous neophiliacs are more likely to possess a “migration gene,” a DNA mutation that occurred about 50,000 years ago, as humans were dispersing from Africa around the world, according to Robert Moyzis, a biochemist at the University of California, Irvine. The mutations are more prevalent in the most far-flung populations, like Indian tribes in South America descended from the neophiliacs who crossed the Bering Strait.

These genetic variations affect the brain’s regulation of dopamine, the neurotransmitter associated with the processing of rewards and new stimuli (and drugs like cocaine).

The variations have been linked to faster reaction times, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and a higher penchant for novelty-seeking and risk-taking.

But genes, as usual, are only part of the story. Researchers have found that people’s tendency for novelty-seeking also depends on their upbringing, on the local culture and on their stage of life. By some estimates, the urge for novelty drops by half between the ages of 20 and 60.

Dr. Cloninger, a professor of psychiatry and genetics at Washington University in St. Louis, tracked people using a personality test he developed two decades ago, the Temperament and Character Inventory.

By administering the test periodically and chronicling changes in people’s lives over more than a decade, he and colleagues looked for the crucial combination of traits in people who flourished over the years — the ones who reported the best health, most friends, fewest emotional problems and greatest satisfaction with life.

What was the secret to their happy temperament and character?

A trio of traits.

They scored high in novelty-seeking as well in persistence and “self-transcendence.”

Persistence, the stick-to-it virtue promoted by strong-willed Victorians, may sound like the opposite of novelty-seeking, but the two traits can coexist and balance each other.

“People with persistence tend to be achievers because they’ll keep working at something even when there’s no immediate reward,” Dr. Cloninger says.

“They’ll think, ‘I didn’t win this time, but next time I will.’ But what if conditions have changed? Then you’re better off trying something new.

To succeed, you want to be able to regulate your impulses while also having the imagination to see what the future would be like if you tried something new.”

The other trait in the trio, self-transcendence, gives people a larger perspective.

“It’s the capacity to get lost in the moment doing what you love to do, to feel a connection to nature and humanity and the universe,” Dr. Cloninger says.

“It’s sometimes found in disorganized people who are immature and do a lot of wishful thinking and daydreaming, but when it’s combined with persistence and novelty-seeking, it leads to personal growth and enables you to balance your needs with those of the people around you.”

In some ways, this is the best of all possible worlds for novelty seekers. Never have there so many new things to sample, especially in the United States, a nation of immigrants, which Ms. Gallagher ranks as the most neophilic society in history.

In pre-industrial cultures, curiosity was sometimes considered a vice, and people didn’t expect constant stimulation. The English word “boredom” didn’t come into popular use until the 19th century.

Today, it’s the ultimate insult — borrrring — among teenagers perpetually scanning screens for something new.

Their neophilia may be an essential skill, just as it was for hunter-gatherers evolving on the savanna, but it can also be problematic.

The urge for novelty, like the primal urge to consume fat, can lead you astray.

“We now consume about 100,000 words each day from various media, which is a whopping 350 percent increase, measured in bytes, over what we handled back in 1980,” Ms. Gallagher says.

“Neophilia spurs us to adjust and explore and create technology and art, but at the extreme it can fuel a chronic restlessness and distraction.”

She and Dr. Cloninger both advise neophiles to be selective in their targets.

“Don’t go wide and shallow into useless trivia,” Ms. Gallagher says.

“Use your neophilia to go deep into subjects that are important to you.”

That’s a traditional bit of advice, but to some dopamine-charged neophiliacs, it may qualify as news.

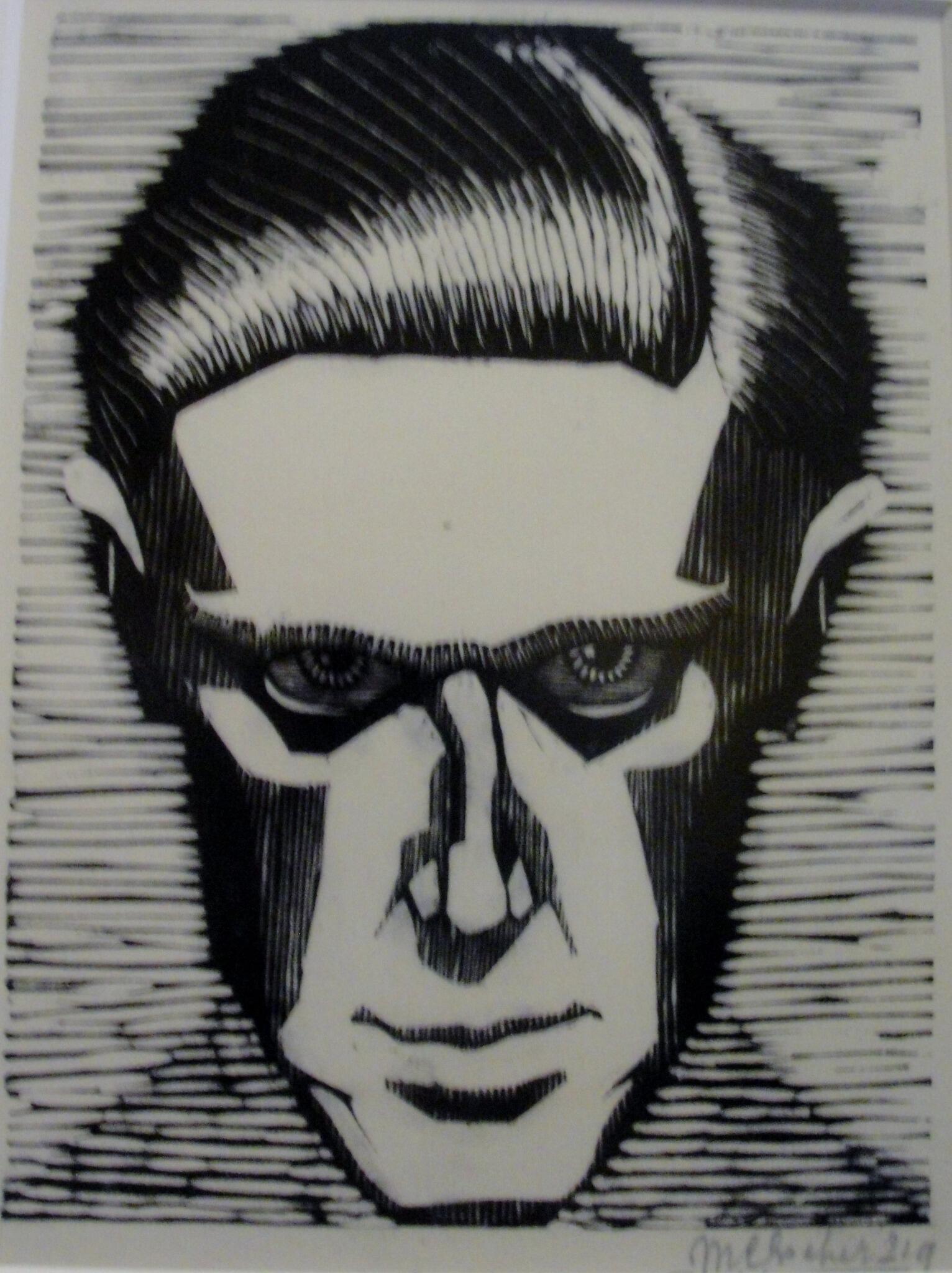

M.C. Escher: Self-Portrait

M.C. Escher's hypnotizing 1919 woodcut self-portrait, as seen at @EscherinPaleis in the Hague: pic.twitter.com/24kCTD4VV6

Saturday, March 23, 2013

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)