Published:

The Age,

A2, July 10, 2010.

WHAT: Sam Jinks

WHERE Karen Woodbury Gallery, 4 Albert Street, Richmond, 9421 2500, kwgallery.com

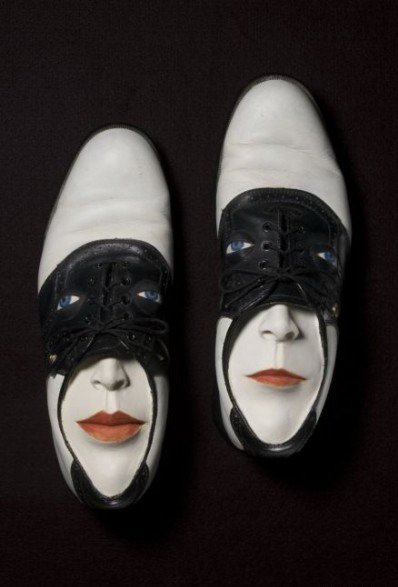

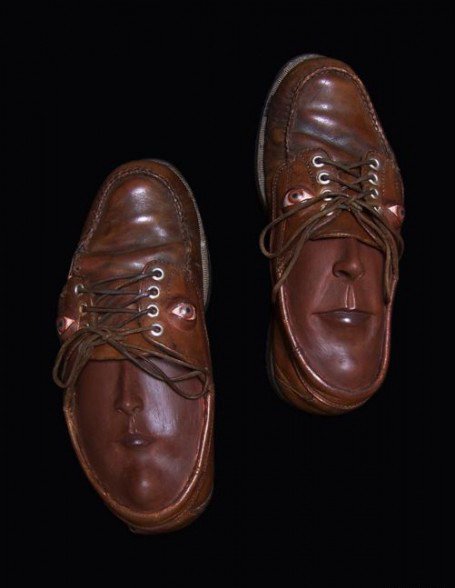

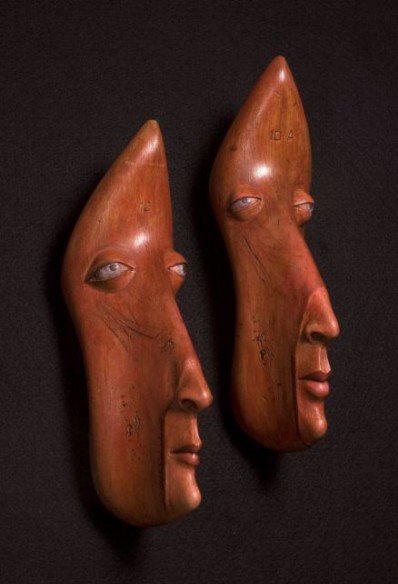

Although both artists would loathe the comparison, it’s hard not to reference Ron Mueck when discussing the incredibly lifelike foam, silicon, paint and human hair sculptures of Melbourne artist Sam Jinks.

His works hold such a resemblance to reality that you can’t help but be immediately affected by their presence; the intricate contours of skin, the weight of the flesh and curve of the implied skeletal structure.

In the same breath, what makes Jinks’ work so engaging is its delicate detours from what we might otherwise frame in terms of “hyperrealism”.

The three works that perch, spotlighted, in an otherwise dimmed Karen Woodbury Gallery each offer a distinct eschewal of scale and context. As we enter the space, two gigantic snails slither together in a seemingly romantic embrace. At normal scale, the gesture would seem innocuous, but their amplified dimensions give it a kind of poignancy and gravity.

To the left of the space, a tiny many crouches under a bed sheet, its fabric clinging to the protruding vertebrae of his emaciated frame. The minute scale only heightens his vulnerability.

The stunning, ever-so-slightly downscaled "Woman and Child" acts as something of a centerpiece.

A frail, beautiful, old woman clutches a tiny newborn to her breast.

It is the embodiment of intimacy and connection. In one scene, we witness the conclusion of one life and the beginning of another in all its sadness, joy and beauty.

It’s a deft summation of Jinks’ work. While our immediate fascination may be one of an almost scientific, anatomical ilk, it is his masterful twisting, shrinking and augmenting of hyper-realism – his shifting of size and setting – that grants these works their elegiac, emotive and very much human potency.

STUDIO VISIT WITH SAM JINKS

Published:

Broadsheet, July 1, 2010.

Sam Jinks’ astonishing sculptures eschew hyperrealism with subtle shifts in scale and dimension. Dan Rule drops by his Coburg studio to chat about his upcoming show at Karen Woodbury Gallery.

Wandering amongst the dismembered bodies, oversized snails, skulls, skeletons and power tools that litter Sam Jinks’ Coburg warehouse/studio is somewhat affronting at first. A lifelike woman’s head perches on a stand connected to the workbench; off to the right, her headless torso holds a newborn baby to its breast. The 37-year-old’s foam, silicon, paint and human hair sculptures are as strikingly human as they are subtly removed from reality. We take the tour and chat with Jinks about human and insect relationships, lineage, his unique practice and his new exhibition at Karen Woodbury Gallery.

How long have you been in your current space?

I’ve been here for 10 months. When I got here I was doing a few editions so I didn’t settle in for ages, then we had this show, so I really don’t feel like I’ve set up the space properly. Upstairs is almost empty. I’m kind of struggling to allow myself to work up there. It’s all carpeted, air-conditioned; it’s just all wrong (laughs). No, but it’s a great studio and it’s close to my home. I was commuting from here to Collingwood everyday before I got this place. It was fine, but when you’ve got an exhibition coming up you tend to work really long hours, so commuting isn’t great in those circumstances. Now I walk five minutes.

I haven’t seen you work with animals before. Is it a very different process to working on human figuration for you?

I used to make a lot of insects, not so much mammals. I always liked the idea of doing things that were really small. Things like frogs, for example, are really quite alien, and so I always found that stuff kind of fun to make. It’s sort of like a different world.

You still have the same sort of technical issues where you’re trying to mould an object and cast it and trying to get it to look reasonably realistic. But with figurative stuff it’s harder in a way, for me, because you have to fool people, because you’re surrounded by people everyday.

But working on non-human forms is kind of liberating as well, to be honest. I think you can say a lot with animals or insects that you can also say with the figure, but it’s almost easier to digest in some ways.

Where do the embracing snails, which will feature in the new show, come from?

Doing things like snails, I find it kind of poetic in some ways. You can kind of separate yourself from it all. It was a real moment for me with these works. Basically I got home at about midnight from a long day at work sculpting some figure and I was really tired. It was quite a damp night and I was just sitting there in the backyard and I just noticed these two snails and kind of watched it all unfold. It was quite moving; I was really kind of struck by it.

The relationship between two insects is almost like a really stripped down version of the relationship between people. All of the stuff is removed and it’s very basic.

I think that’s a really interesting idea – this stripped back, elemental, but equally powerful relationship.

Yeah, it’s almost an easier way to digest the world, looking at something like that, when there’s that bit of separation. It’s easy to apply to your own situation. It’s kind of tragic.

Your work has an uncomfortable, but at the same time, comforting sensibility about it. Just watching you take the baby’s head from the body before was quite confronting, I guess, because of that intense realism. How does that dynamic work with you? Do you drift in and out of connection with the work?

Yeah, I do. That’s a good way of putting it. Because, you know, there’s the practical side where you have to make something and you have to really wring its neck sometimes to even get it to look even plausible. I’ve never been one for total realism. I don’t think I have the physical energy for it and, you know, life’s too short. It’s like a hyper-realistic painting; it’s not something that’s very exciting to look at. So I always change the dimensions of bits and some bits are bigger than they should be and other bits are smaller…

But you do kind of drift in and out of connection, because you’re dealing with silicon rubber and paint and bits of hair all in isolation, then you’ve got to try and combine it in some sort of way inside a mould and as a sculpture to make it realistic. I think at the end things start to come together and you can kind of interact with the work, but only then. Like, I’m installing some of this work tomorrow and it’ll probably only be at that moment that I have that experience. Well, hopefully I have that experience (laughs).

There’s a lovely sense of possibility with these new works, especially the work with the old woman holding the baby. It’s not just the end of one life, but the beginning of another…

I guess I’ve also just had the experience of having a child and watching my mother hold the baby and just going ‘Wow, there its all is, it’s all combined in the one thing’. It’s like all the one thread. It’s all very strange, I think, and this work is kind of me trying to come to grips with that a bit. When you hold your own child, you’re sort of holding yourself in many ways and it’s a bit kind of sobering.

Tell me about your relationship with Ron Mueck.

We’re good friends and we’ve known each other for a long time, but we’ve never actually worked together. We’ve talked a lot about the work over the years and he’s given me a lot of great advice, but now it kind of feels like ‘Who’s going to do that great thing?’. I mean, Ron’s kind of the grand master because he’s been doing it for a long time now. There’s another guy in Canada, Evan Penny, who has been doing it for a long time, but there aren’t a lot of people who do it as art. There are a lot of people who pay other people to do it for them and there’s always a look to that kind of work.

So I guess there’s a kinship. Ron’s a nice guy too, which kind of makes it hard in a way. I sometimes I wish I didn’t like him so much (laughs). It would be much easier to just loathe him (much laughter). But he’s a really cool guy. He’s quite incredible too. He’s got a very rare quality.

There’s often a kind of scientific engagement and fascination with this kind of work…

Yeah, but I think it’s changing, which is a good thing. When I first started doing it as art it was really about making it look realistic. It was like ‘Look, it’s got hair’, you know, but that’s not what it’s about anymore and it’s good, in a way, that it’s moved beyond that. It’s a useful tool, but if someone can really make something beautiful, that’s the ultimate goal. It shouldn’t just be about making something look real. It’s pointless in a way and is kind of a bit of a futile pursuit in a way, because it’s endless.

I like things to look a little separated from reality. It’s nice to walk into a gallery and be transported just a little bit, as opposed to being transported back to where you already are.

Sam Jinks new exhibition opens at Karen Woodbury Gallery Wednesday June 30 and runs until July 24.

www.samjinks.com

![AROUND THE GALLERIES Dan RulePublished: The Age, A2, July 10, 2010.

WHAT Sam JinksWHERE Karen Woodbury Gallery, 4 Albert Street, Richmond, 9421 2500, kwgallery.com

Although both artists would loathe the comparison, it’s hard not to reference Ron Mueck when discussing the incredibly lifelike foam, silicon, paint and human hair sculptures of Melbourne artist Sam Jinks. His works hold such a resemblance to reality that you can’t help but be immediately affected by their presence; the intricate contours of skin, the weight of the flesh and curve of the implied skeletal structure. In the same breath, what makes Jinks’ work so engaging is its delicate detours from what we might otherwise frame in terms of “hyperrealism”. The three works that perch, spotlighted, in an otherwise dimmed Karen Woodbury Gallery each offer a distinct eschewal of scale and context. As we enter the space, two gigantic snails slither together in a seemingly romantic embrace. At normal scale, the gesture would seem innocuous, but their amplified dimensions give it a kind of poignancy and gravity. To the left of the space, a tiny many crouches under a bed sheet, its fabric clinging to the protruding vertebrae of his emaciated frame. The minute scale only heightens his vulnerability. The stunning, ever-so-slightly downscaled [start italic]Woman and Child[end italic] acts as something of a centrepiece. A frail, beautiful, old woman clutches a tiny newborn to her breast. It is the embodiment of intimacy and connection. In one scene, we witness the conclusion of one life and the beginning of another in all its sadness, joy and beauty. It’s a deft summation of Jinks’ work. While our immediate fascination may be one of an almost scientific, anatomical ilk, it is his masterful twisting, shrinking and augmenting of hyperrealism – his shifting of size and setting – that grants these works their elegiac, emotive and very much human potency. Wed to Sat 11am–5pm, until July 24.

WHAT Drew Pettifer: Hold onto your friendsWHERE No No Gallery, 14 Raglan Street, North Melbourne, 0405 968 618, nonogallery.org

Young Melbourne photographer Drew Pettifer’s erotic portraits and video work invoke intimacy and uneasiness in equal measure. Capturing his young, handsome male muses amid the rolling pastures and spectacular rural backdrops of his youth and childhood, Pettifer effectively imposes an urban queer aesthetic onto a landscape that espouses a very different kind of narrative. In the photographs, the often naked subjects play and pose confidently against the landscape. In one, “Dan” stands, head turned, among a forest of tall pines, his erect penis jutting out, perpendicular to the rest of the scene. In another, “Dylan” lurches from rock to rock, his naked body glowing against sprawling green. The video offers a rather different vantage. Slow, telescopic zooms eventually reveal two male figures in dense forest scenes, against towering mountainsides and on empty beaches, standing straight on, a hand placed on one other’s genitals. The young men seem awkward, lost, vulnerable in the extreme, the ominous voyeuristic gaze zooming ever closer. The difference between the bodies of work is stark. Indeed, while the photographs and video seem to both offer a kind of autobiographical engagement with a place and background, they each tell a very different chapter of the tale. Thurs to Sat noon–6pm, until July 24.

WHAT Anne Zahalka: The Way Things AppearWHERE Arc One Gallery, 45 Flinders Lane, city, 9650 0589, arc1gallery.com

This new series of works by celebrated Australian photomedia artist Anne Zahalka hones its focus on art’s interface with the public. Her handsome, large-scale prints capture fragments, nooks and crannies of various major public art museums – London’s National Portrait Gallery and the Art Gallery of New South Wales included – offering a first or second-person vantage of the just how the public engages with art. While the first-person photographs take the form of snapshots, giving an immediate sense of just what the audience observes in the gallery, the meticulously composed second-person photographs offer far more layers of interest. We not only sight the work, the viewer and a cropped corner of the gallery’s interior, but are led to consider the spatial, psychological and behavioural relationships at play in these major monuments to art. Tues to Sat 11am–5pm, until July 24.

WHAT Mike Parr: The Hallelujah ChorusWHERE Anna Schwartz Gallery, 185 Flinders Lane, city, 9654 6131, annaschwartzgallery.com

Known internationally for his often extreme forays into the testing of his physical and psychological limits, Australian printmaker and performance artist Mike Parr offers up a comparatively palatable, nonetheless visceral serve of new works over both floors of Anna Schwartz Gallery. The main focus is his massively scaled unique prints, which are rendered with a spectacular melange of raw details, scrawls and textures to form an odd strain of self-portraiture. The video work, Cartesian Corpse captures a recent, 34-hour endurance piece performed at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. Tues to Fri noon–6pm, Sat 1pm–5pm, until July 24.](http://24.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_l5yic10VTT1qa3c8ao1_400.jpg)