Humphry Osmond, The Man Who Coined “Psychedelic”

Work with psychedelics[

edit]

See also:

Psychedelic drug

After the war, Osmond joined the psychiatric unit at

St George's Hospital, London where he rose to become

senior registrar. His time at the hospital was to prove pivotal in three respects, firstly it was where he met his wife Amy "Jane" Roffey who was working there as a nurse, secondly he met Dr

John Smythies who was to become one of his major collaborators, and thirdly he first encountered the drugs that would become associated with his name (and his with theirs): LSD and mescaline. While researching the drugs at St George's, Osmond noticed that they produced similar effects to schizophrenia and he became convinced that the disease was caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain. These ideas were not well received amongst the psychiatric community in London at the time.

[2][3][4] In 1951, Osmond and Smythies moved to

Saskatchewan, Canada to join the staff of the

Weyburn Mental Hospital in the southeastern city of

Weyburn, Saskatchewan.

At Weyburn, Osmond recruited a group of research psychologists to turn the hospital into a design-research laboratory. There, he conducted a wide variety of patient studies and observations using

hallucinogenic drugs, collaborating with

Abram Hoffer and others. In 1952, Osmond related the similarity of

mescaline to

adrenaline molecules, in a theory which implied that schizophrenia might be a form of self-intoxication caused by one's own body. He collected the biographies of recovered schizophrenics, and he held that psychiatrists can only understand the schizophrenic by understanding the rational way the mind makes sense of distorted perceptions. He pursued this idea with passion, exploring all avenues to gain insight into the shattered perceptions of schizophrenia, holding that the illness arises primarily from distortions of perception. Yet during the same period, Osmond became aware of the potential of psychedelics to foster mind-expanding and mystical experiences.

In 1953, English-born

Aldous Huxley was long-since a renowned poet and playwright who, in his twenties, had gone on to achieve success and acclaim as a novelist and widely published essayist. He had lived in the U.S. for well over a decade and gained some experience screenwriting for Hollywood films. Huxley had initiated a correspondence with Osmond. In one letter, Huxley lamented that contemporary education seemed typically to have the unintended consequence of constricting the minds of the educated—close the minds of students, that is, to inspiration and to many things other than material success and consumerism. In their exchange of letters, Huxley asked Osmond if he would be kind enough to supply a dose of mescaline.

[5]

In May of that year, Osmond traveled to the Los Angeles area for a conference and, while there, provided Huxley with the requested dose of mescaline and supervised the ensuing experience in the

author's home neighborhood.

[6] As a result of his experience, Huxley produced an enthusiastic book called

The Doors of Perception, describing the look of the Hollywood Hills and his responses to artwork while under the influence. Osmond's name appears in four footnotes in the early pages of the book (in references to articles Osmond had written regarding medicinal use of hallucinogenic drugs).

Osmond was respected and trusted enough that in 1955 he was approached by

Christopher Mayhew (later, Baron Mayhew), an

English politician, and guided Mayhew through a mescaline trip that was filmed for broadcast by the BBC.

[7]

Osmond and Abram Hoffer were taught a way to "maximize the LSD experience" by the influential layman

Al Hubbard, who came to Weyburn. Thereafter they adopted some of Hubbard's methods.

[8]

Humphry Osmond first proposed the term "psychedelic" at a meeting of the

New York Academy of Sciences in 1956.

[9] He said the word meant "mind manifesting" (from "mind", ψυχή (

psyche), and "manifest", δήλος (delos)) and called it "clear, euphonious and uncontaminated by other associations." Huxley had sent Osmond a rhyme containing his own suggested invented word: "To make this trivial world sublime, take half a gram of phanerothyme" (θυμός (thymos) meaning 'spiritedness' in

Ancient Greek.) Osmond countered with "To fathom Hell or soar angelic, just take a pinch of psychedelic"

[10][11] (Alternative version: To fall in Hell or soar angelic / You'll need a pinch of psychedelic.).

[12]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humphry_Osmond

BMJ. 2004 Mar 20; 328(7441): 713.

PMCID: PMC381240

Humphry Osmond

Janice Hopkins Tanne

Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Go to:

Short abstract

Psychiatrist who investigated LSD, “turned on” Aldous Huxley, and coined the word “psychedelic”

Humphry Osmond was at the cutting edge of psychiatric research in the 1950s. He believed that hallucinogenic drugs might be useful in treating mental illness and he studied the effects of LSD on people with alcohol dependency. His investigations led to his association with the novelist Aldous Huxley and to involvement with the CIA and MI6, which were interested in LSD as a possible “truth drug” to make enemy agents reveal secrets.

Was Osmond ahead of his time? His work was cut short by the 1960s drugs backlash, and only now is his work with hallucinogens being looked at with new interest.

Humphry Osmond was born in Surrey in 1917 and graduated from Guy's Hospital Medical School. During the second world war he served in the navy as a ship's psychiatrist. After the war, at St George's Hospital, he and Dr John Smythies learnt of the chemist Albert Hofmann's work with the hallucinogenic drug LSD-25 in Switzerland. They thought schizophrenia might be caused by metabolic aberrations producing symptoms similar to those from drugs such as LSD and mescaline.

“Osmond was interested in a metabolic redefinition of schizophrenia as something like diabetes,” said a former colleague, California psychiatrist Dr Tod Hiro Mikuriya.

LSD-25 had been synthesized by Hofmann in 1938; he discovered its hallucinogenic properties in 1943. One day when he worked with the chemical he felt restless and dizzy and went home. Over the next few hours he experienced fantastic, vivid images with intense colours. He thought he had probably absorbed a small amount of the chemical.

During the 1940s and 1950s both scientists and government intelligence agencies were interested in using hallucinogenic drugs such as mescaline and LSD as a “truth drug”.

Osmond, the scientist, thought the hallucinogens might help treat mental illness. He later wrote, “Schizophrenics are lonely because they cannot let their fellows know what is happening to them and so lose the thread of social support. LSD-25, used as a psychotomimetic, allows us to study these problems of communication from the inside and learn how to devise better methods of helping the sick.” Some psychiatrists thought they should take LSD to

understand what their patients were experiencing.

The psychiatric establishment was not interested in drugs. In 1951 Osmond moved to Canada, to a bleak institution called the Weyburn Mental Hospital in Saskatchewan, where he had good research funding from the Canadian government and the Rockefeller Foundation and worked with a biochemist colleague, Dr Abram Hoffer. The hospital had many alcoholic patients who had not responded to all previous treatments. Osmond thought that hallucinogenic drugs produced symptoms similar to delirium tremens. Producing a terrifying artificial delirium might frighten an alcoholic into change. Between 1954 and 1960, Osmond and Hoffer treated about 2000 alcoholics under carefully controlled conditions.

They were astonished by what they found. In an interview with the psychiatrist Dr John Halpern, associate director of the substance abuse research programme at Harvard's McClean Hospital, Dr Hoffer recalled, “Many of them didn't have a terrible experience. In fact, they had a rather interesting experience.” Osmond and Hoffer reported that 40% to 45% of the alcoholics who were treated with LSD had not returned to drinking after a year.

Osmond sought a name for the effect that LSD has on the mind, consulting the novelist Aldous Huxley who was interested in these drugs. Osmond and Huxley had become friends and Osmond gave him mescaline in 1953. Huxley suggested “phanerothyme,” from the Greek words for “to show” and “spirit,” and sent a rhyme: “To make this mundane world sublime, Take half a gram of phanerothyme.” Instead, Osmond chose “psychedelic,” from the Greek words psyche (for mind or soul) and deloun (for show), and suggested, “To fathom Hell or soar angelic/Just take a pinch of psychedelic.” He announced it at the New York Academy of Sciences meeting in 1957.

But the climate was changing in the cultural and political turmoil of the Swinging Sixties. The use of marijuana and other recreational drugs among young people was thought to be a cause of social unrest, environmental protests, women's lib, civil rights marches, and protests against the Vietnam war. “The money dried up,” said Dr Halpern, and new laws restricted researchers' ability to study the drugs. “Osmond was at the cutting edge of psychiatric research at the time. It was a tragedy his work was shut down because of the culture,” said Dr Charles Grob, professor of psychiatry at the University of California School of Medicine-Los Angeles (UCLA).

Osmond moved to head the Bureau of Research in Neurology and Psychiatry at the New Jersey Psychiatric Institute in Princeton. His colleague Dr Mikuriya, later in charge of marijuana research at the National Institute of Mental Health, was puzzled that Osmond and his colleagues had psychedelic drugs available in their offices when local police had undercover agents searching for drug users. He found the answer 20 years later when the book Acid Dreams revealed Osmond's CIA and MI6 connections.

Osmond later moved to the University of Alabama, where he was professor of psychology until his retirement in 1992. He leaves a wife, three children, and five grandchildren.

Humphry Fortescue Osmond, psychiatrist and researcher, former professor of psychology University of Alabama, United States (b Surrey, United Kingdom, 1917; q Guy's Hospital Medical School 1942), died from a cardiac arrhythmia on 6 February 2004.

Articles from The BMJ are provided here courtesy of BMJ Publishing Group

Formats:

Article |

PubReader |

ePub (beta) |

PDF (108K) |

Citation

Humphry Osmond

Links https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC381240/

Taxonomy

Humphry Osmond

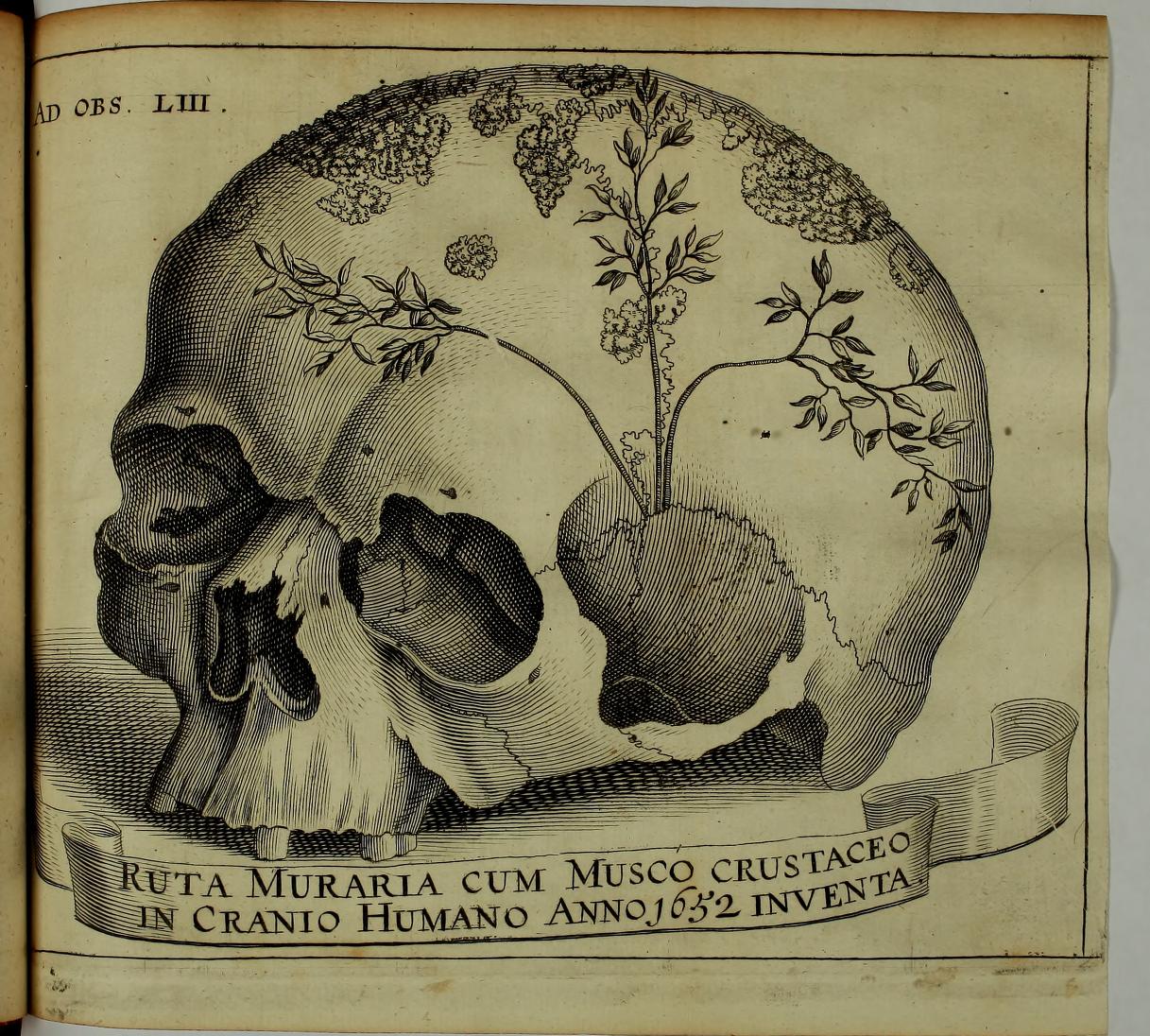

Morbid Anatomy @morbidanatomy 17h17 hours ago From Miscellanea curiosa medico-physica academiae naturae curiosum, 1671. via @BioDivLibrary http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/150750#page/7/mode/1up …

Morbid Anatomy @morbidanatomy 17h17 hours ago From Miscellanea curiosa medico-physica academiae naturae curiosum, 1671. via @BioDivLibrary http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/150750#page/7/mode/1up …

Dr. Gemma Angel @Gemma_Angel Dec 2 Romany Reagan (@msromany) on one of my favourite subjects: death & eroticism #MarginalDeath

Dr. Gemma Angel @Gemma_Angel Dec 2 Romany Reagan (@msromany) on one of my favourite subjects: death & eroticism #MarginalDeath

Sarah Troop @wunderkamercast Dec 2 The skull of St Benedictus in Muri, Switzerland. Photo by Paul Koudounaris

Sarah Troop @wunderkamercast Dec 2 The skull of St Benedictus in Muri, Switzerland. Photo by Paul Koudounaris

Sarah Troop @wunderkamercast Dec 2 November’s done w/. The blown leaves make bat-shapes, web-winged & furious Sylvia Plath, Dialogue Over A Ouija Board

Sarah Troop @wunderkamercast Dec 2 November’s done w/. The blown leaves make bat-shapes, web-winged & furious Sylvia Plath, Dialogue Over A Ouija Board

Lindsey Fitzharris @DrLindseyFitz 10h10 hours ago Victorian mermaid. Disney lied to us, people. More info here: http://ow.ly/SlsZB

Lindsey Fitzharris @DrLindseyFitz 10h10 hours ago Victorian mermaid. Disney lied to us, people. More info here: http://ow.ly/SlsZB

Lindsey Fitzharris @DrLindseyFitz 9h9 hours ago Allegory of the Transience of Life (c.1480).

Lindsey Fitzharris @DrLindseyFitz 9h9 hours ago Allegory of the Transience of Life (c.1480).